More than 600 generations have come and gone, lived their lives, and left subtle footprints in the sands along the river.

Prehistory in Grand Canyon National Park extends back in time thousands of years. The first people to encounter the Grand Canyon did so during the late Pleistocene, when megafauna such as mammoths and extinct ground sloths still roamed the region. Since that time and all the way to the modern day, people have made use of Grand Canyon resources and called the canyon home. Read more below or watch the Grand Archaeology slideshow here.

Paleoindian (13,000 to ca. 9800 years ago)

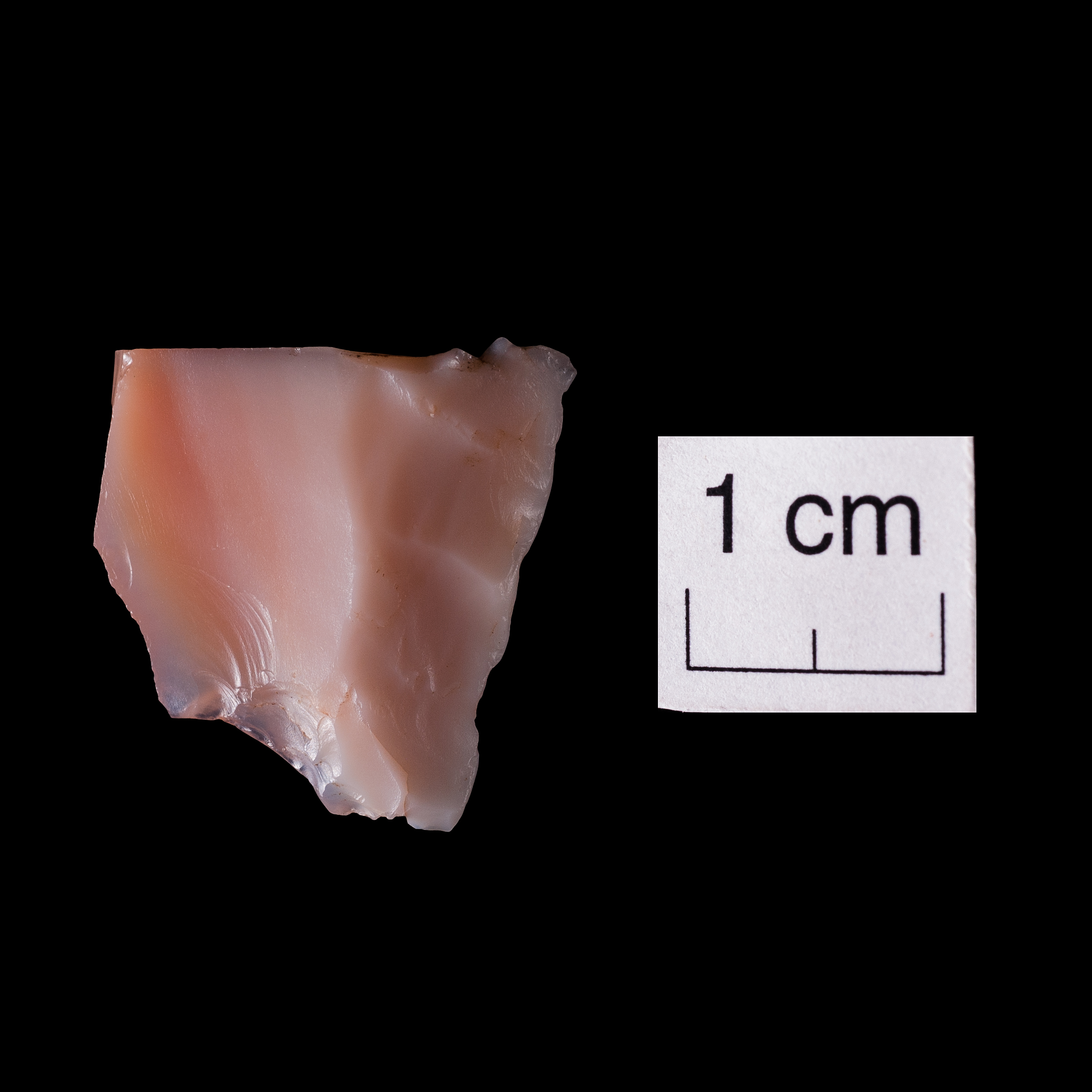

Evidence of the first people to encounter the Grand Canyon is scant, consisting of only a few fragmentary points that once tipped spears or atlatl darts.

The first of these points appears to have been made by a Clovis flintknapper some 13,000 years ago. Clovis people are largely thought to have been the first occupants of the Southwest, and were highly skilled in the art of making stone tools, which were vital to their hunter-gatherer way of life.

Pictured: The Grand Canyon Clovis point was made on Narbona Pass chert, a type of stone from New Mexico. From source to loss in the Desert View area of Grand Canyon National Park, this is a straight-line distance of more than 200 miles (320 km).

Within the next few thousand years, another Paleoindian point was left in the Grand Canyon, this time during the Folsom era. The point is made on Tolchaco chert from the Little Colorado River area, which gives some idea of the path taken to reach Nankoweap where the point was found. Learn more…

A hallmark of the Paleoindian period is big-game hunting. Although archaeologists do not know to what extent big game factored into everyday diet, we do know that Clovis people hunted mammoth and other megafauna in the Southwest, and that Folsom hunters focused on bison in particular.

Archaic (ca. 9800 to ca. 3000 years ago)

The transition between the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Grand Canyon and greater Southwest corresponds to increasing temperatures, increased summer monsoon rainfall, and major changes in flora and fauna. By the start of the Archaic, the megafauna of the preceding period were gone, and vegetative communities had begun to look much like they do today.

Artifacts common to the broad sweep of the Archaic period are notched projectile points, sandals, baskets, and groundstone tools used to process plants and seeds. Large cooking features called roasting pits or thermal ovens are also frequently found at Archaic sites, and certain rock art styles (e.g., Glen Canyon Linear, Esplanade, and Tusayan) date to this period as well.

One of the most fascinating Archaic period developments is that of the split-twig figurine complex. These figurines were made using split willow twigs carefully wrapped to depict sheep, deer, and other game animals, many of which are pierced with sticks reminiscent of atlatl darts. In the Grand Canyon, these figurines are found in cave settings, and are generally thought to have been a form of totemism related to hunting. Learn more…

Preformative/Early Agricultural (3000 to 1500 years ago)

Perhaps as early as 4000 years ago, people began farming corn on the Colorado Plateau. Current evidence for the Grand Canyon, however, suggests the earliest use of corn was around 2300 years ago and that hunting and gathering remained a substantial part of subsistence during this and later periods.

It remains unknown how corn agriculture came to the Grand Canyon, but its arrival is associated with the Basketmaker II archaeological cultural, evidence of which is found in rockshelters with storage features and corncobs and other perishable remains such as cordage and basketry, a single pit house village in the Grand Canyon, certain projectile point forms, and rock art, including the Snake Gulch, Cave Valley, and Preformative variants A and B.

Formative/Ceramic/Pueblo (1500 to 750 years ago)

The Formative period begins with the appearance of ceramic artifacts in the archaeological record of the Grand Canyon, with the bow and arrow also adopted near the beginning of the period. During this time, not only corn, but squash and cotton were being farmed, and people may have moved seasonally from rim to river and back to tend these crops. Initially, people continued to live in pit house structures, but these gave way to above-ground masonry structures ranging from single rooms to multiroom, multistory buildings called pueblos.

The Formative period begins with the appearance of ceramic artifacts in the archaeological record of the Grand Canyon, with the bow and arrow also adopted near the beginning of the period. During this time, not only corn, but squash and cotton were being farmed, and people may have moved seasonally from rim to river and back to tend these crops. Initially, people continued to live in pit house structures, but these gave way to above-ground masonry structures ranging from single rooms to multiroom, multistory buildings called pueblos.

The overall population of the Grand Canyon area at this time does not appear to have ever been particularly high and peaked around 850 years ago. People living in the Grand Canyon during this period had connections to and/or were part of four major archaeological cultures—Cohonina, Kayenta, Virgin, and Patayan—each with their own pottery styles, and to a lesser extent, architectural styles.

Tusayan Ruin, located on the South Rim, was one of the sites occupied in Grand Canyon National Park during the twelfth century A.D. and is fairly typical of small villages at that time, with a U-shaped alignment of rooms dedicated as living space and capped with storage rooms, a kiva nearby, and a farming area not far removed from the pueblo (explore the 3D model here or learn more from the NPS website [link opens in new window]).

For reasons that remain unclear, but that were likely related to larger trends of migration in the Southwest, the pueblo-dwelling people of the Grand Canyon began to leave, so that in as little as 100 years, there were few to no inhabited pueblos remaining in the region.

Protohistoric (750 to 250 years ago)

The departure of pueblo-dwelling people from the Grand Canyon marks the beginning of the Protohistoric period, during which use of the canyon by surrounding Native peoples appears to have been far more sporadic and short-term. By the end of this period in 1776, when the Spanish exploration party led by Dominguez and Vasquez documented their encounters with Havasupai and Southern Paiute people in the Grand Canyon region, the cultural landscape was much changed, and would continue to be so as more and more Euroamericans entered the area.

The archaeological record for this period is sparse compared to the preceding period, but shows evidence of use of the Grand Canyon by ancestral Pai, Southern Paiute, Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo people. Likewise, contemporary Native traditional knowledge reflects the ties of modern Native communities to the Grand Canyon, which is a place held sacred by 11 traditionally associated tribes.

Introductory sidebar quote from The Archaeology of the Grand Canyon: Ancient Peoples, Ancient Places, edited by F.E. Smiley, C.E. Downum, and S.G. Smiley, 2017. Grand Canyon Association.