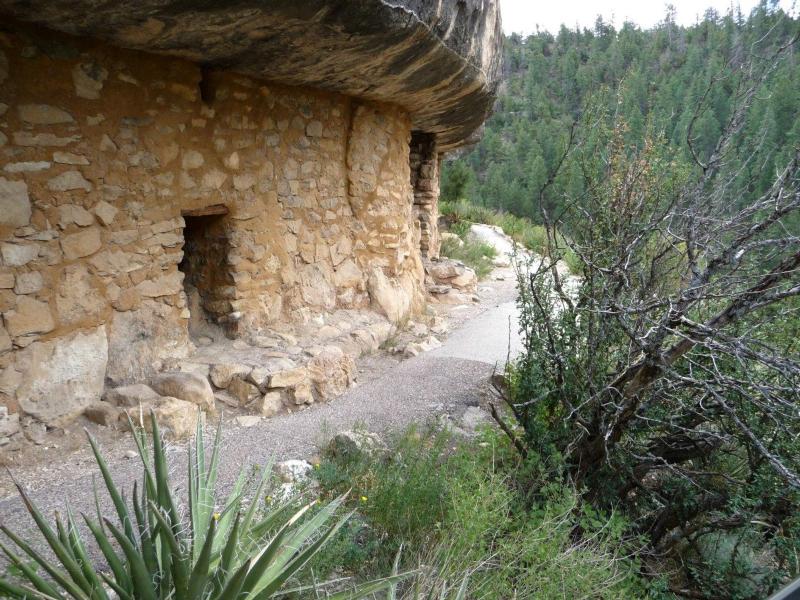

Cliff Dwelling, Walnut Canyon National Monument. Photo Credit: National Park Service.

Walnut Canyon National Monument was established to protect the Sinagua cliff dwellings built into the canyon alcoves. The Monument and surrounding lands contain hundreds of archaeological sites dating primarily from A.D. 1000 to the A.D. 1200s, but also inclusive of occupation periods both preceding and succeeding that date range. Learn more…

Featured exhibit

Explore the rock art imagery of Walnut Canyon through 3D models, 360-degree panoramas, and other advanced imaging techniques supplemented with textual and video commentary.

- Explore Rock Art

- Panel H

- Verde Incised

- Basketmaker Pictographs

- Sinagua Pictographs

- Apache Pictographs

- By a Seasonal Waterfall

- WACA 209 Panel B

- WACA 209 Panel A (bottom)

- WACA 209 Panel A (top)

Additional features of the Walnut Canyon Virtual Museum include a 360-degree panoramic virtual tour of the trails at Walnut Canyon, a video of the 1993 flood of Walnut Creek—a rare but impressive phenomenon—and a brief prehistory of the canyon (below).

- 360 Virtual Tour

- 1993 Flood Video

A Brief Prehistory . . .

Human history at Walnut Canyon is likely about as old as any place in North America, extending back to the Paleoindian period, when people made their living by hunting game animals and gathering wild plant foods. Evidence for the earliest of these periods was found only 25 miles north at Wupatki National Monument in the form of a Clovis projectile point, and at Walnut Canyon, includes a later-period Eden-style projectile point base, indicating use of the canyon extends back at least 10,000 years.

Ten thousand years ago is also the approximate date at which modern vegetation communities and climatic regimes began to take hold and the point in time at which the 6000-year period known by archaeologists as the Archaic also began. During the Archaic period, hunting-gathering lifestyles persisted, but with a greater emphasis on plant resources and perhaps more permanency in territory than during the preceding period.

Evidence for Archaic period land use at Walnut Canyon is generally limited to lithic artifacts, including debris from making stone tools and dart points of various styles. A yucca quid (a small mass of yucca leaves chewed by human beings) found beneath later pueblo remains, however, also indicates use of the natural shelters provided by the alcoves of Walnut Canyon during this period.

With no other artifacts present to indicate long-term use, this quid likely reflects only a brief stay. An intriguing set of artifacts found in a different shelter, however, suggests that Walnut Canyon also served as a place for ancient rituals in which hunters symbolically acted out the hunt. These consist of figurines made from splitting and weaving together willow and other branches to depict deer and other large game animals frequently pierced with a small twigs representing spears or darts. Similar artifacts are found from the Verde Valley to the south and the Grand Canyon to the north, and were made between about 5,000 and 3,000 years ago.

By the latter date, and perhaps as early as 4,000 years ago, hunter-gathers began to make use of maize agriculture. In the northern Southwest, this period is referred to as the Basketmaker era, divided by archaeologists into Basketmaker II (2000 BC – AD 500) and Basketmaker III (AD 500-700), and named such to honor the exquisite basketry and other woven items found in early agricultural sites. Beyond the adoption of cultivation practices, these periods also encompass the advent of bow-and-arrow technology, and near the end of the Basketmaker III period, pottery manufacture, as well.

The Basketmaker era in and around Walnut Canyon is represented by only a few stylistically distinct projectile points, rock art, and a handful of early pottery. In fact, thus far, only ten sites within Walnut Canyon can be securely dated to this period and into the AD 1000s, with these consisting of scattered small farmsteads located near soils fit for cultivation.

Major changes, however, would come with the eruption of Sunset Crater volcano, located just 15 miles to the north, in the last quarter of the 11th century. Believed to have occurred over a period of months to a few years, the eruption would have been visible to people living as far away as western New Mexico, and when complete, had blanketed much of the region in a thin layer of volcanic cinders thought by many to have provided a water-retaining mulch contributing to the success of local farmers in the greater Flagstaff area.

The curtain of fire from the Sunset Crater volcano eruption would have been visible at great distances.

Perhaps drawn by the eruption, people with connections to the Hohokam archaeological culture of central Arizona established new villages downstream of Walnut Canyon. Here they built Hohokam-style ballcourts, used Hohokam-style shell jewelry and pottery, and in some instances, adopted the Hohokam burial practice of cremation.

Hohokam influence in the region faded during the early 12th century, and new changes were underway. People began to build small pueblos across the Flagstaff area, and in some locations, including Wupatki to the north, more massive constructions that would later emerge as central places. At one site located east and downstream of Walnut Canyon, people also used Douglas-fir for roof beams, the only likely source of which was Walnut Canyon itself.

Walnut Canyon’s farmers grew maize, beans, and squash supplemented with wild plant and animal foods. Though working in an arid, unpredictable, and often cold environment, they were also successful in the cultivation of cotton.

The majority of Walnut Canyon’s cliff dwellings were built and occupied between AD 1140 and AD 1220, with only limited evidence at a few sites suggesting use after AD 1250. Population estimates suggest the Walnut Canyon community was likely small, with no more than around 175 people living there at the peak of population in the late 1100s.

Archaeologists refer to the residents of the Walnut Canyon cliff dwellings as the Sinagua, a term that links them through material culture to other people living in the Flagstaff area and down into the Verde Valley during the same broad period of time. Certain aspects of Walnut Canyon architecture and rock art, however, suggest that within Walnut Canyon developed certain unique styles not readily related to other Sinagua sites in the region.

Some of these distinctive features may have developed because of functional needs specific to living in Walnut Canyon. The stone steps or landings around entrances, for example, may have helped mitigate problems with mud and snow, and the ventilation systems built into the cliff dwellings would have helped circulate fresh air into rooms where open fires were in use. Some features may also have had duel purposes. The extraordinarily thick walls of the rooms at Walnut Canyon, for example, may have offered some degree of thermal regulation, keeping the rooms warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer, but may also have been designed to afford privacy to the occupants, a concept that may also be reflected the lack of internal connections (doorways) between rooms in the Walnut Canyon cliff dwellings.

The large room sizes and some of the rock art of Walnut Canyon are more enigmatic, and the latter particularly so. While some rock art in Walnut Canyon is comparable to the general Sinagua rock art repertoire, pictographs (painted rock art) occur with a frequency at Walnut Canyon that is uncommon elsewhere in the Flagstaff region, and in one instance, mirror imagery—rare in regional rock art overall—is also depicted in a panel known as “The Twins.”

Whatever the meaning of Walnut Canyon’s unique rock art and architectural attributes, these were left behind when the cliff dwellers began to move out of Walnut Canyon in the early 13th century. The large rooms and lack of interior doorways connecting the rooms at Walnut Canyon, for example, do not appear at later-dating sites in the Flagstaff area, nor at even later sites across the region. Likewise, though there is color continuity in some of the pictographs made in Walnut Canyon in the centuries after the cliff dwellers left, the design elements are significantly different.

Why the builders of the Walnut Canyon cliff dwellings left also remains uncertain, though it seems likely that several periods of cold climate and declining agricultural yields may have played significance roles. Other factors may have involved local political struggles, social unrest, or prophecy or other beliefs requiring that the people move on.

Walnut Canyon was not the only place from which people moved during this period; by AD 1300, virtually no one was living in the Flagstaff area year-round. At around the same time, a recognizably Hopi cultural pattern was developing to the east and south, and at some towns on the Hopi mesas and in the Verde Valley, population also soared. That the former residents of Walnut Canyon joined at least some of these villages is likely, and today’s Hopi people recognize this connection. Other Native peoples, including Navajos, Havasupais, Yavapais, Apaches, and Hualapais, also have stories and terminology relating to Walnut Canyon and its residents; some of these connections are ancient, some more recent, but all are profoundly meaningful to modern Native people who remember the canyon in their oral traditions and recognize it as a sacred cultural landscape.

Adapted from:

Downum, Christian E. (2016) Homes of Stone, Place of Dreams: Walnut Canyon’s Ancient People. Plateau 9(1):33-78.

Additional information for Walnut Canyon National Monument is available at the official National Park Service website for Walnut Canyon (link opens in new window).