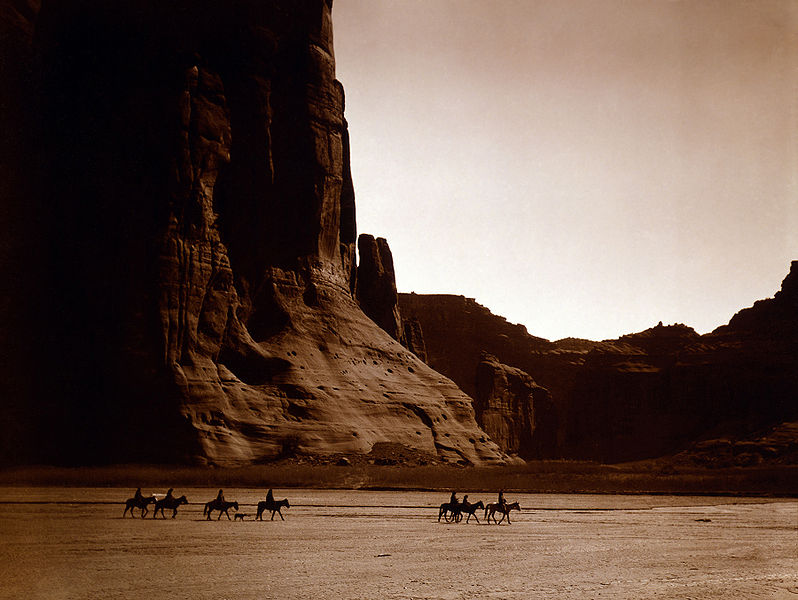

Navajo Riders in Canyon de Chelly, ca. 1904. Photo Credit: Edward S. Curtis; Original image held in the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540, USA; Call Number: LOT 12311.

Broadly speaking, the Historic period in the Southwest begins as early as A.D. 1539 – 1540 with the journeys of Fray Marcos de Niza and Francisco Coronado, both Spanish explorers in search of the seven cities of Cibola. However, in many regions, direct interaction between Native people, the Spanish, and later, Euroamericas, did not occur until much later. Like the preceding Protohistoric period, the Historic period in the Southwest was a period of interaction, and often, conflict. For Native American cultures in the Southwest, the Historic period was largely one of conquest, first by the Spanish, and then by Euroamericans, but it was also a period of cultural change in which non-Native foods, technology, livestock, and religion were adopted and/or incorporated into Native traditions. Adoption of horses by Plains cultures, for example, changed substantially the mobility, subsistence patterns, and interaction spheres of many Plains people. Likewise, for Navajo people, sheep became an important food and wool source. Native American culture change during this period was also a result of conflict-driven interactions. For example, during the late 1700s, Comanche and Ute raiding, combined with Spanish rule, drove Pueblo people into Navajo communities, and with them came new skills and technology, religious ideas, and ceremonial practices that where incorporated into Navajo life.

Additional cultural changes results from the late 1800s and early 1900s establishment of Indian Reservations in the Southwest. Removal to Reservations not only displaced Native people from their traditional homelands, but also created situations of dependency on European goods and lifeways. In 1879, the Bureau of Ethnology was established to record and study Native peoples in the United States. As ethnologists and anthropologists attempted to relate contemporary Native people to the ruins around them, Southwestern Archaeology also began to develop as a field of study. Unfortunately, for a long period of time, the relationship between archaeologists and Native Americans was characterized by, at minimum, a lack of communication, and at worst, and utter disregard for Native tradition. However, since the passage of the Native American Graves Repatriation and Protection Act and concurrent amendments to the National Historic Preservation Act in the 1990s, archaeologists and Native people have worked to restructure how archaeology is practiced in the Southwest. Many Southwest tribes have also taken control of archaeology and preservation on Tribal lands, establishing tribal-based heritage programs like the Zuni Archaeology Program, Navajo Nation Archaeology Department, the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, and the Gila River Indian Community Cultural Resource Management Program. Although not always smooth, collaborative efforts have produced new methods and interpretive paths, and more importantly, generated a mutual respect.

Featured Image: Additional information can be found here (link opens in new window).