The Desert View Watchtower in Grand Canyon National Park was designed by architect Mary Colter in the 1930s for the Fred Harvey Company. Colter based her design on prehistoric architecture in Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, Chaco, and Wupatki, using stone native to the Grand Canyon to encase a steel frame, and commissioned Hopi artist Fred Kabotie to paint the walls of the Hopi Room, the first level of the tower. Fred Geary, artist for the Fred Harvey Company, painted the walls and ceilings of the second and third floors with designs from prehistoric sites across the Southwest, and Chester Dennis, another Hopi artist and lead Hopi dancer at the dedication of the Watchtower in 1933, added incised petroglyph designs.

~All photographs used on this page are by Michael Quinn, National Park Service, unless otherwise noted. Additional historic photos can be found here on the Virtual Museum.

First floor

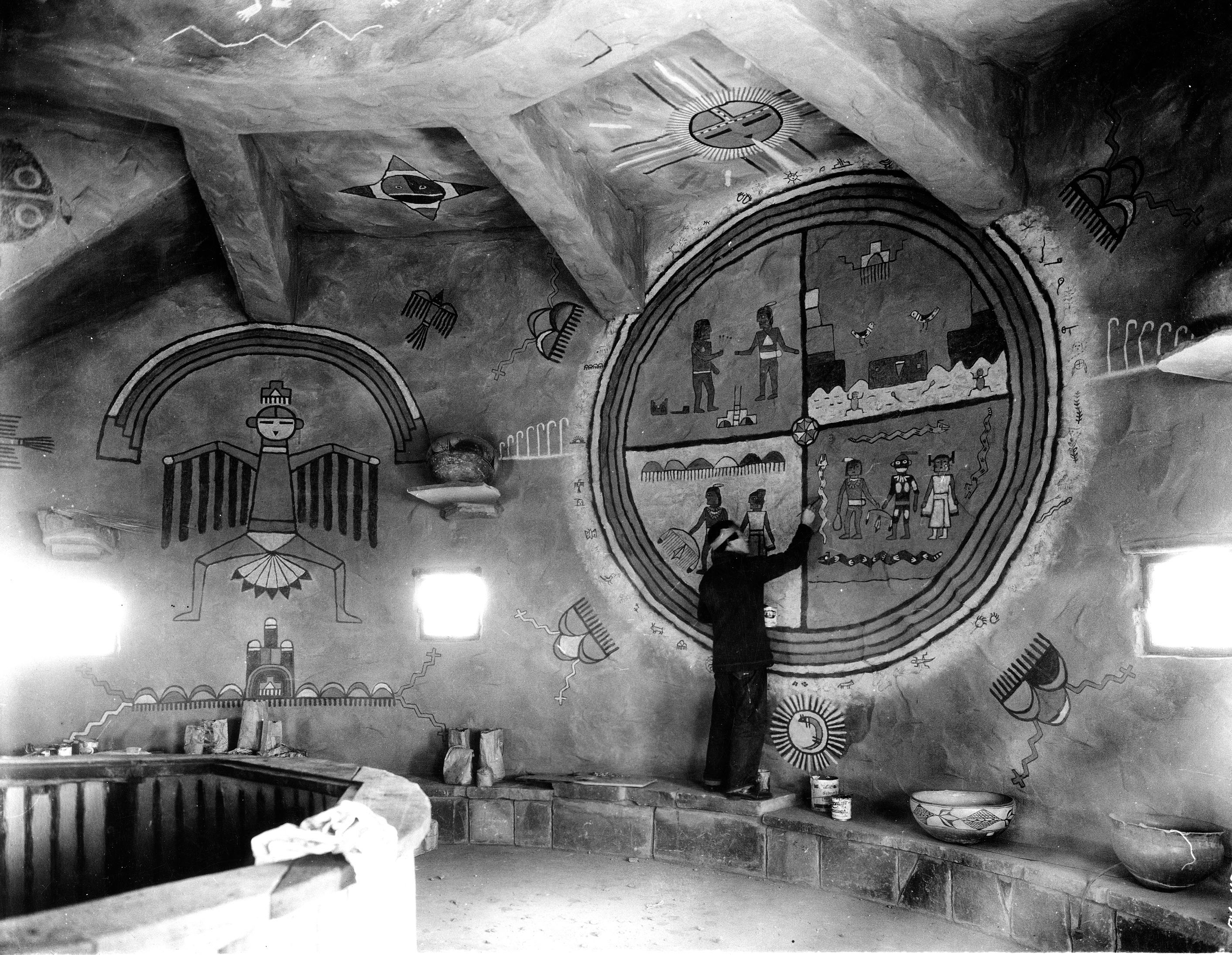

The first floor of the Watchtower is the Hopi Room, painted by Fred Kabotie. The central design is a large circular painting depicting the Hopi Snake Legend— the story of the Chief’s young son who was the first man to navigate the Colorado River and who later became the first Snake Priest.

Fred Kabotie painting the Hopi Room Snake Mural, ca. 1932 (Fred Harvey Company photo, NPS Catalog No. 8801a).

Excerpted below are Kabotie’s explanations of his murals, as provided in Mary Colter’s 1933 book Watchtower at Desert View and its Relation, Architecturally, to the Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest, reprinted (link opens in new window) with illustrations by the Grand Canyon Association in 2015.

~The story begins in the upper left-hand corner where the father gives the prayer sticks to the son. Their kiva is shown at their feet. The upper right-hand section shows the boat floating down the Colorado River…In the lower right-hand corner is depicted the Snake Priest giving the bow symbol (Aoat natsi) of the Snake Clan to the Chief’s Son. The ‘beautiful maiden’ stands beside her father. The lower left-hand corner shows their honeymoon trip back. Because of the blessing of the Snake People upon them, the bow is shown in action, dripping rain, and above them are all the different rain clouds, six in number.~

“This is the story of the Chief’s young son. He lived at Navajo Mountain, some say, and came to the Grand Canyon with the elders to get salt and also paints for their sacred ceremonies. But he know the Great River even before that, for it passes very near to the Sacred Mountain where he lived. The ceaseless flowing of the water fascinated him. He sat on the bank all day long and wondered where the water went. ‘It must be very full there, where all the water goes!’ His abstraction was noted by his father who reasoned with the youth to no purpose. ‘I want to see for myself,’ said the boy. So, the father consented and helped him find a suitable log—one big enough so that it would be hollowed into a boat. Then they made a lid for it so it could be entirely closed except for a hole through which a pole might be thrust to keep it off the rocks. The Priest—the young man’s father—made Bahos, or prayer sticks, for him to take along and his aunts prepared food for him.

When all was ready, a bed of turkey’s downy breast feathers was made for him in the bottom of the boat and the voyage began.

The four colors (symbolic of the Universe) are used for the background of this legend because it begins with the home of the young son of the Hopi Chief, in the north, represented by yellow; carries west in his journey, represented by the turquoise blue; then south, which is red; ending in the east which is white… in the heart of the circle is the design that represents the center of the universe… the four colors around the circle represent Light and Life… the white band surrounding the rainbow border is the Path of Life and in it are drawn the signs of the clanship of the Hopi Tribe… some being shown shown definitely as representing clans that have always been and still are powerful. Some are only shadows, representing clans that are extinct; some are drawn faintly and then redrawn plainly—these are the clans that almost ‘died’ but are reviving.

Not much is told of the adventures by the way but when he arrives at his destination life begins in earnest for him. He goes first to the Spider Woman and wins her favor with his father’s prayer sticks. So she promises to help him in his adventure. He wishes to find the ‘Kiva-in-the-West’—the place where the Sun rests in the evening. In one form of the legend—that told by Kabotie—he seems to have been sidetracked before finding it. In this legend he immediately is met by a beautiful maiden who takes him to the Snake Kiva where he meets her father, the Snake Priest. Here, advised by the Spider Woman who sits behind his ear, we wins out in various tests of courage; one in particular, where during a Snake Ceremony he seizes and hands onto the most hideous of the snakes and tames it by courage and magic, at which it resumes the shape of the beautiful maiden who had met him at his arrival. The Snake People approve of him and the Snake Priest teaches him all the ritual of the Snake Ceremony and gives him the sacred bow (Aoat natsi) used in the Snake Ceremony to this day. He is also given the Mana (girl) in marriage, as well as a bag of turquoise wampum, and is told to return to his own people. If ever he needs the help of the Snake People, they promise him he has only to perform the ceremonial dance he has been taught by them and they will come to his assistance.

The way home is bless with rain and shine, and he and his bride are warmly welcomed on their arriving at his father’s kiva.

However, the offspring of this couple turn out to be little snakes and bite the Hopi children, to the great indignation of the whole village. The wide, whose feelings are much injured by the Hopi attitude toward her children, finally advises returning her babies to her own people where they will be better understood. The young chief takes them back to the Ocean Kiva. While their next children have not the characteristics of the first, the Hopi are always fearful they will bite. Civil discord arises from this state of mind and the Hopi who have in the past lived together at Navajo Mountain, start out on their wanderings—some clans or families in one direction and some in another. Our Snake Chief and his family wander about until they reach the vicinity of Walpi. The Hopi on the mesa have suffered greatly from the lack of rain for a very long time. Ever since the little Hopi snake children had been sent back to the Snake people, their maternal relatives had been feeling bitterly toward the Hopi people, and as they had the rain in their keeping it had been withheld from the mesas. Our young Snake Priest told the people of Walpi that he could act as mediator between the Hopi and the Snake People if they would take him and his family into their village. He and the Snake Princess and their family were warmly welcomed and settled down at once. He made his claim good by establishing in Walpi, the Snake Fraternity and immediately performed the very first Snake Dance. It was blessed with much rain and at once became an established rite. The Snake Dance—best known of all Ceremonial Dances of the Hopi Indians—is held every fall and immediately the rain descends and the floods are opened—as many can affirm who have stalled in the arroyos on the way back to civilization after one of the weirdest experiences of a lifetime.”

Other portions of the first floor mural depict the Ages of Man’s Life, the Sun, the Moon, the Power of the Air, the Course of the Sun, Muyingwa—God of Germination, the Women’s Dance, Flower Symbols, a Hopi Wedding, the Little War God, the Star Priest, the Twin War Gods, the Little God of Echo, and Rainbow Clouds and Flowers. The soffit of the balcony is painted with the Great Snake, and the ceiling of the room is decorated with stars, including the Evening and Morning stars (the Guardians of the Sun), the Milky Way, Women’s Dance, shooting stars, the North Star, Pleides, and the Dipper.

The Ages of Man’s Life – One each side of the circle of life are processions of cane (Natungpi) representing the ages of man.

The procession from the east represents the growth of man from childhood to where manhood is ‘inlet’ (the word is Kabotie’s own) into the Universe. The ‘outlet’ on the west represents manhood down to old age, gradually dwindling in stature to the grave.

The Sun and the Moon – The Sun is depicted above this circle. ‘The Sun is looked up to as a sacred father of all living beings—the Medicine man or the giver of life. For this reason the Sun is represented as having all the colors of the Universe, and here is shown with the breath of eternal life spraying medicine on the people as he circles them.’ The symbol of the moon is shown at the bottom of the design.

- The Sun

- The Moon

Power of the Air – Hay-a-pa-o, the large winged figure on the left of the main circle represents the powers or forces of the air. A rainbow ending in clouds is above him, and a rain cloud is over his head—and the birds fly around him.

Directly below him is a ‘universal cloud’ symbol dropping rain. Note the six cloud forms used instead of the usual four. These Cloud Symbols represent the Hopi’s six directions—north, west, south, and east—to which are added ‘above’ and ‘below.’ To the four colors previously given—yellow for north; turquoise blue or green for west; red for south; white for east, are added—black for ‘above’ and brown for ‘below.’ (The six clouds are also shown in the quarter of the shield of the legend, recording the return of the Snake Priest).

At both ends of the cloud symbols are shown forked lightning symbols. The forked lightning are messengers of the gods.

Course of the Sun – To the right of the main circle is a rainbow with sacred kivas at both ends. This represents the course of the Sun during the day. We rises from his ‘Kiva-in-the-East’ and the Rainbow shows his path above the world. The world is represented by the symbol for the ‘Four Worlds’ and the rays going to the four directions are the ‘Four Paths’ or ways.

Course of the Sun – To the right of the main circle is a rainbow with sacred kivas at both ends. This represents the course of the Sun during the day. We rises from his ‘Kiva-in-the-East’ and the Rainbow shows his path above the world. The world is represented by the symbol for the ‘Four Worlds’ and the rays going to the four directions are the ‘Four Paths’ or ways.

At the top of the Rainbow is shown the ‘Seat of the Sun’ where he rests a moment at noon before he begins to descend to his ‘Kiva-in-the-West.’ On reaching the ‘Kiva-in-the-West’ he refreshes himself with a little sleep and then begins the night journey under the world and at dawn reaches the ‘Kiva-in-the-East’ once more. Every day and night is a repetition of this same journey of the Sun around the world.

The black snakes outside the kivas are the guards of the sacred kivas at all times.

Muyingwa—God of Germination – Continuing to the right, the next picture represents the God of Germination—Muyingwa. The cornstalk is in his right hand; in his left are the planting stick and the bag containing seeds; also a gourd containing the water with which to water the seeds.

Both the Sun and Moon attend him and over his head is shown the rain cloud. Like the Sun, the God of Germination is represented as having many ‘colors’ with which to develop the various plants, but he requires assistance from the outside powers shown in his attendants—for he needs the sun for its head; the clouds for their rain; and the moon for its influence over the time of germination.

Women’s Dance – The next picture is the symbol of the Lalakontu Dance. Lalakontu is a Women’s Secret Society. The constellation that is the basis of this society is shown in the ceiling panel above.

Flower Symbols – The two upright designs made of triangles with the points down, one placed above another, always represent flowers. Kabotie says that flower lovers paint these designs in their homes and that they stand for ‘every kind of flower.’

Flower Symbols – The two upright designs made of triangles with the points down, one placed above another, always represent flowers. Kabotie says that flower lovers paint these designs in their homes and that they stand for ‘every kind of flower.’

Hopi Wedding – Above the flower symbols is shown a Hopi wedding. Note the bride with her hair done in the squash-blossom whorls, the style the Hopi maiden wears. She is attended by two matrons with hair in braids. The matrons carry basket plaques heaped with meal, while the bride’s is heaped with piki of her own baking. The shooting stars in the ceiling panel above are scattering around her the ‘sacred meal’ form their tails, which are composed of this magic-making material.

The Little War God – ‘The little black fellow’ standing next is Pookongahoya—the Little War God. He is also the God of Defense. He is shown with bow and arrow in his hands. At his feet are the ball and stick of the game he favors—a kind pf hockey played with a puck made of pitch and sand. The two snakes are his attendants. (He acts as the main Katcina [sic] in the Snake Dance and a snake is one of his symbols.) Above him is his war shield bearing the sign of the star—two short parallel lines. The ends of lightning rods project on four sides of the shield. The shield itself means ‘Defense’ and the lightning rods are the ‘Powers of Destruction.’

The Star Priest – The star-headed figure seen to the right of this Pookongahoya is the Star Priest, who is usually classed with the ‘Warrior group.’

Twin War Gods – The Pookongahoyas are twins and the other twin is shown on the wall of the stairway. Sometimes these twins are spoken of as if they were but one god. They and Ballongahoya, the Little God of Echo, are the grandchildren of Spider Woman—a very important person, indeed! They are always spoken of as ‘little’ and always as ill-favored. When not engaged in making war, they play boisterous games and are full of pranks and tricks. Always making trouble for others and always getting into it themselves. They provide the slapstick comedy of every story—at once fools, knaves, and heroes, falling into dire calamity but inevitably coming out on top—even to the wining of ‘the beautiful maiden!’

Little God of Echo – Over the door is the Little God of Echo—Baloongahoya. He is the little brother to the Pookongahoyas, and just another of the same kind. He carries the bullroarer in one hand and bow and arrow in the other. (There is a very strong echo in the Tower; hence Baloongahoya over the door!).

Rainbow Clouds and Flowers – Over this figure is a rainbow ending in falling rain clouds. The rain falls on the flower symbols. This is a ‘very great blessing’ over a door to a room.

Evening and Morning Stars – To the left of the Sun is depicted the Evening Star. Mi-hek-shu-ho is his name take from the word meaning ‘Night.’ To his right is the Morning Sta. Tal-a-shu is his name taken from the word for ‘Light.’ ‘The Morning Star is said to still guard the entrance of the Sun in the front; the Evening Star the entrance of the Sun in the rear.’

Milky Way – To the right of the Morning Star comes the Milky Way, the Paths of Good and Bad People. The long and continuous line is the path of the good; its branch, which is short, is the path of the evil.

Women’s Dance – Next, to the right, is a circle of stars with only two stars in the enclosure. These stars represent the dance, Lalakontu (one of the women’s societies), a ceremony and dance performed in the late summer. This group of stars is our Corona borealis, a conspicuous constellation which is overhead about nine in the evenings of July.

Shooting Stars – When a shooting star is seen, it is taken for granted that the star is off to officiate at a wedding, spilling some of the sacred cornmeal from his brilliant tail over the bride. Shooting stars are lucky—a sign of plenty and prosperity.

North Star – The North Star is known as Que-nink-shu.

The Pleiades – Kabotie writes: There is a group of stars that always cling together like mud and they are called by that name ‘Chochookam.’ (We call them the Pleiades).

The Dipper – In the next panel (over the stairway) ‘are the three shining stars in their same position eternally—called Hotumcomu. They are directly overhead by midnight during winter.’ Kabotie probably means the North Star and two pointers of the Dipper.

The Great Snake – Completing the ceiling decoration is painted on the soffit around the balcony parapet, the Great Snake, who carries on his body, repeated many times, the symbol the Priests use on their ceremonial kilts in the Snake Dance. He is the father of all serpents—the Great Plumed Snake that goes back to the farthest prehistoric times and is shown with the Koshare in the caves at Abo.

Second and Third floors

The second and third floors of the Desert View Watchtower were painted by Fred Harvey Company artist Fred Geary. Geary copied his designs from prehistoric sites all over the Southwest, including locations in Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.

By origin, Geary’s (or Kabotie’s or Dennis’s, if noted) second and third floor designs include the following:

Arizona

Adamana (Painted Desert) – Chundees and other petroglyphs.

Canyon de Chelly – meader/fret/maze design and other pictographs.

Chevlon Ruin – design copied from a gravestone by Fred Kabotie.

Grand Canyon – pictographs from cliff dwellings.

Navajo National Monument cliff-dwellings – mythical animals, blanket-like designs, thunderbird, maze, mountain sheep, and war god (Betatakin); and maze, ‘frieze of nine turkeys’ (Keet Seel).

Petrified Forest – animals, birds, human figures (both male and female), footprints, spirals, flute player, zigzags and snakes, flowers/corn/yucca, mythical creatures, maze/meander, mountain, and double lightning designs from petroglyphs.

Polacca (or near to) – Dado recreated from drawings of a kiva mural lost to rain only days after excavation.

Sikyatki Pueblo – mountain lion and man design recreated from a pottery design.

Walpi (or near to) – Man-eagle.

Unknown, but probable Arizona origin – petroglyphs made by Hopi artist Chester Dennis on the second and third floor parapets.

Colorado

Mesa Verde – Dado design, also found at Canyon de Chelly and Ute Mountain Tribal Park.

New Mexico

Abo Caves – Koshare and snake, plumed serpent, star frog, thunderbird, yellow Katsina, medallion, snake in circle, animals, insects, masks, hand prints, and geometrical symbols. ~ The roof of Abo Cave was painted over many, many times over a long period of time, such that no portion was left blank.

Looking up at the “Abo Cave” ceiling in the Desert View Watchtower, with Chester Dennis’s petroglyphs visible within the parapets.

Jemez Pueblo – Flute Ceremony and Rainbow in the West.

Mimbres Ruins – fishing pelican, horny toad, and hare on a crescent moon from pottery designs.

Rito de los Frijoles – ‘Rabbit in the Baby Basket,’ Katsina, and dancer (etchings).

San Cristobol – sun shield and animal designs.

Willow Springs – Kowemsi, “mudhead” designs based on petroglyphs.

Utah

Petroglyphs, including Fremont designs.

Fourth floor

The fourth and final floor of the Watchtower was left without decoration, as Colter did not want the interior to detract from the panoramic views of the Grand Canyon offered from that floor. This level instead serves as an observation deck.

Learn More:….

Colter, Mary Elizabeth Jane. (1933) Watchtower at Desert View and its Relation, Architecturally, to the Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest, reprinted (link opens in new window) with illustrations by the Grand Canyon Association in 2015.

Grattan, Virginia L. (1992) Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth. Northland Press, Flagstaff.

National Park Service Desert View webpage (link opens in new window).