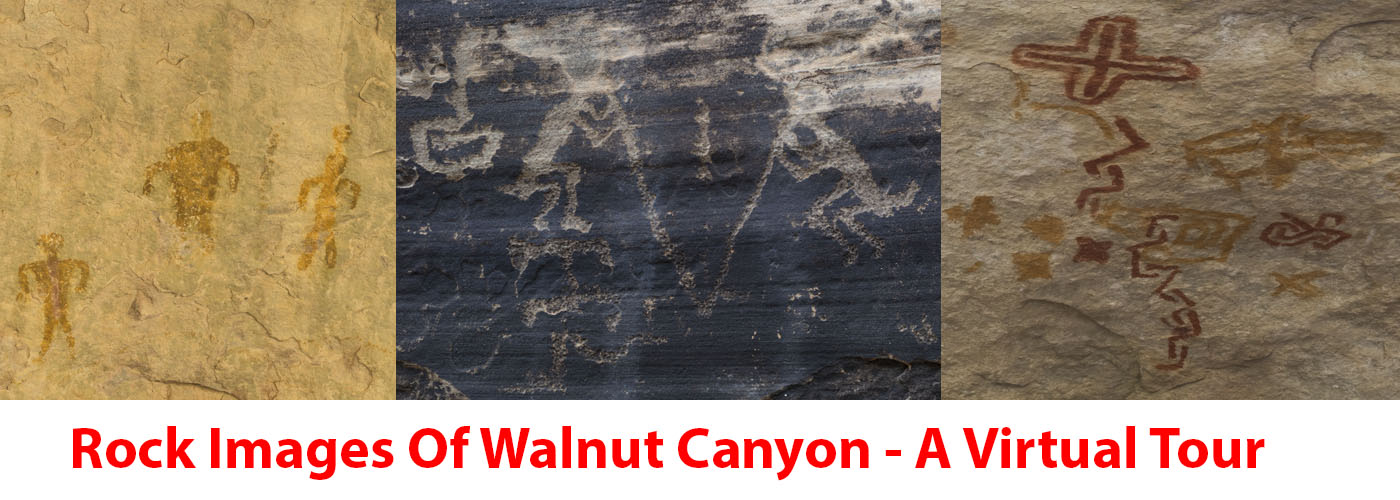

Thousands of years before Walnut Canyon was established as a national monument, the canyon landscape was the homeland for the ancestors of today’s Hopi, Zuni, Havasupai, Hualapai, Yavapai, Navajo, Apache and Paiute peoples. The Walnut Canyon Rock Images Virtual Tour formally acknowledges past and present traditionally associated communities.

- Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation

- Havasupai Tribe

- Hopi Tribe

- Hualapai Tribe

- Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians

- Navajo Nation

- San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona (link 2)

- San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe of Arizona

- Tonto Apache Tribe of Arizona

- White Mountain Apache Tribe

- Yavapai-Apache Nation

- Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe (link 2)

- Zuni Tribe

Within this website, descriptions of rock imagery and interpretations of their design, function and meaning are based on an archaeological perspective based on best available information. From this perspective, there is a considerable lack of information pertaining to the design, function and meaning of Walnut Canyon’s rock imagery; however, archaeological information can serve as a basis for future investigation including documentation and interpretations, as well as a complement to Native American perspectives. Visitors certainly will benefit from learning the contribution of rock imagery to Walnut Canyon’s rich history and gain an appreciation for the need to protect and preserve these sites.

Walnut Canyon National Monument is a part of the Flagstaff Area National Monuments, which also includes Wupatki National Monument and Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument. Established in 1915 by President Woodrow Wilson’s proclamation, the purpose of Walnut Canyon National Monument is:

To preserve and protect ancient Northern Sinagua cliff dwellings, pit houses, and other cultural resources found in the canyon’s deeply incised and meandering topography. Perched on natural promontories and nestled in alcoves, these resources, of great ethnographic, scientific, and educational importance, provide public inspiration and enjoyment.

The Monument was managed by the United States Forest Service from 1915 until September 24, 1938, when management was transferred to the National Park Service.

Following historic exploration of northern Arizona and the completion of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad to Flagstaff in 1882, Walnut Canyon and its cliff dwellings were a popular tourist destination for Flagstaff locals and railroad visitors wishing to see ancient “ruins” of what they assumed was “a lost civilization.” These early tourists and explorers partook in several practices that severely damaged archaeological resources. For example, it was common practice to loot pots (ceramic vessels) and other artifacts from the rooms, and to explode whole walls of cliff dwellings with dynamite to improve the lighting conditions for digging. Unfortunately, it is impossible to know the quantities and types of cultural materials have been lost to looting, but the damage was irreversible.

Since the creation of the Monument, and the ratification of further legislation protecting archaeological sites, the Federal Government is obligated to project all natural and cultural resources of Walnut Canyon for the enjoyment of present and future generations for years to come.

For more info, visit the official National Park Service page for Walnut Canyon National Monument (link opens in new window). See also the page for Walnut Canyon NM at the Southwest Virtual Museum.

Native American – Past and Present

Walnut Canyon National Monument protects over 500 archaeological sites along the ten miles of Walnut Creek. Due to its ecological diversity and varied terrain, Walnut Canyon was an ideal place for habitation and resource gathering in the arid environment of the Colorado Plateau. The area surrounding the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, AZ has a long history of human occupation. Archaeologists have documented artifacts, primarily Clovis projectile points, in the area dating to 13,000 years ago. Within Walnut Canyon National Monument, archaeologists have found artifacts, primarily projectile points, that date to 7000 BCE (Before Common Era, formerly BC). While these early gatherers and hunters did not leave evidence of permanent dwellings, they no doubt relied on this area for its abundant and rich resources. The culture best-known for building stone masonry alcove houses in the canyon were the Sinagua, who inhabited the canyon from around 1100-1250 CE (Common Era, formerly AD). The term Sinagua is an archaeological term first used by the Founder of the Museum of Northern Arizona Harold Colton to describe the unique ceramic vessels, stones masonry houses in the broader Flagstaff area. Sinagua occupation away from Walnut Canyon lasted from 550 CE – 1300 CE: see description below. Today, the Hopi Tribe trace their ancestry back to many pre-Columbian cultures including the Sinagua and refer to their ancient ancestors as “Hisatsinom”, a term meaning “those who lived long ago“.

For more information on the Native American cultures associated with Walnut Canyon, visit the “Native American Cultures Of Walnut Canyon” web page (link on the right or bottom).

Geology

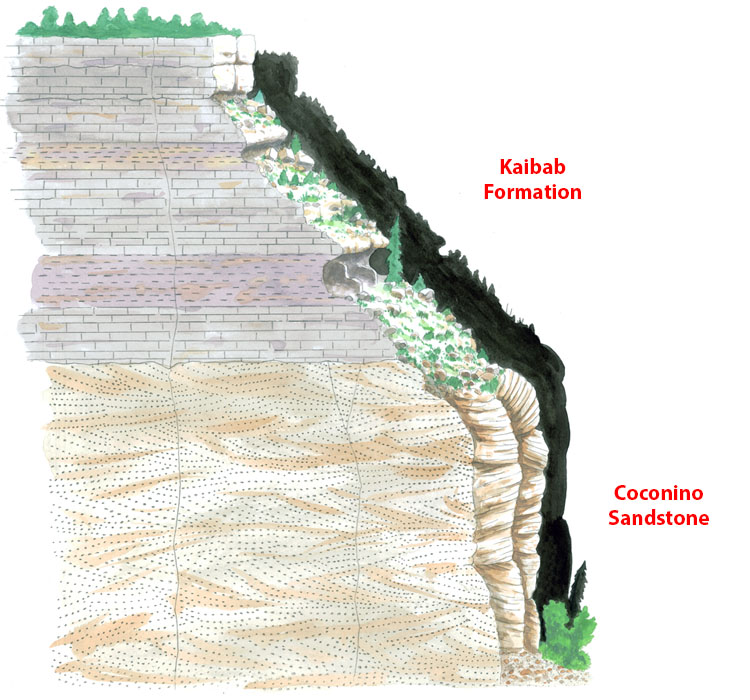

Walnut Canyon is located 10 miles southeast of downtown Flagstaff, Arizona, and roughly 4 miles south of Interstate 40. The canyon runs 12 miles along the western and northern edge of Anderson Mesa, with 10 miles winding its way through the heart of Walnut Canyon National Monument. Starting six million years ago, Walnut Creek cut this ancient canyon 400 feet through several distinct geological layers that shaped the biodiversity and history of the canyon. The Coconino Sandstone forms the steep, inner gorge of the canyon, and shows this region was once home to sweeping Sahara-like sand dunes from the cross-bedded layers they left behind. The Kaibab Formation, mainly limestone, created the sloping and cliff banded upper canyon. In the cliff banded layers, hard erosion-resistant limestone makes up the ceilings of alcoves while softer limestone immediately beneath harder layers has eroded over the millennia to form natural alcoves. The terms alcove and overhang are sometimes used interchangeably; alcove is the entire structure of an enclosed recess in a cliff face while overhang is the upper portion of the shelter that forms the ceiling. These naturally-occurring alcoves provided ideal locations for building stone masonry walls to enclose living and storage rooms that the Monument is now famous for. To read more about the natural features and ecosystems, refer to the Walnut Canyon National Monument website.

Geologic cross-section of Walnut Canyon (Figure: Zach Zdinak)

Biology

The region acts as a biodiverse transition zone with plants and animals typical of highlands, lowlands, desert environments, and cooler temperate environments. The canyon ecosystem has approximately 400 species of plants, including Gambel oak, ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, Utah juniper, Rocky Mountain juniper, banana yucca, pinyon pine, Stansbury cliffrose, fernbush, and prickly pear cactus. The canyon’s ancient inhabitants used many of the plants for food and medicine. Researchers have identified 121 bird species, 69 mammal species, and 28 species of amphibians and reptiles. Some of these species include the Rocky Mountain elk, coati, mule deer, grey fox, great horned owl, and various hawks and falcons. The Mexican spotted owl, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, finds secluded nesting areas within the protected monument borders.

From rolling, open plains on the plateau to the deeply incised microclimates of the canyon, Walnut Canyon’s environments contains vast differences in topography resulting in the creation of various habitats for a range of plant and animal species. The region acts as a biodiverse transition zone with plants and animals typical of highlands, lowlands, desert environments, and cooler temperate environments.

The south-facing slopes of Walnut Canyon (left) receive more direct sunlight, and are warmer and drier than the north-facing slopes (right). The vegetation on the south-facing slopes (e.g. cactus, yucca, and juniper) tend to be more heat and drought tolerant than the species (Douglas fir, Ponderosa Pine) that grow on the north-facing slopes. Above the rim, forests of Ponderosa and pinyon pine dominate. At the bottom of the canyon, where more water is available, you’ll find water-loving riparian species such as walnut, ash, cottonwood, and willows (Photo: Northern Arizona University)

Researchers have identified 121 bird species, 69 mammal species, and 28 species of amphibians and reptiles. Some of these species include the Rocky Mountain elk, coati, mule deer, grey fox, great horned owl, and various hawks and falcons. The Mexican spotted owl, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, finds secluded nesting areas within the protected monument borders. Click the links for more information on the animals, plants, and environment.

The coati (or coatimundi) is normally found in southern Arizona into Mexico, but has established a home at Walnut Canyon (Photo: Jongleur100 [Public domain])