The Wupatki Pueblo Trail is a self-guided trail 1/2 mile (0.8 km) in length and taking approximately 45 minutes to complete in person. The trail is paved with steps and inclines, and is wheelchair accessible to the overlook, and beyond with assistance.

Knowledgeable Hopis feel the proper place name for this area in Nuvaovi (the place of the snow) and the site known today as Wukoki was Wupatki.

The farming settlement of Wupatki was unique. To appreciate why, we have to start by thinking big. From roughly AD 400 to 1700, culture in the Southwest was distinguished by farming, pottery, villages, seasonal moves, and large-scale migrations. Major settlement systems were in place by AD 1100 in Chaco Canyon, the Phoenix Basin, and northern Mesoamerica. With favorable climates for agriculture and room to grow, the Southwest’s farming population was reaching a peak.

Until the mid-1100s, Wupatki remained a “frontier” between established groups defined by archaeologists as Sinagua, Cohonina, and Kayenta. Then, in one of the warmest, driest places on the Colorado Plateau, life flourished. This became a densely populated landscape supporting a complex society where people, goods, and ideas converged.

“For its time and place there was no other pueblo like Wupatki. It was in all probability the tallest, largest, and perhaps the richest and most influential pueblo in the area.” ~E. Brennan and C. Downum, Report of Findings: Prestabilization Documentation for Wupatki Pueblo

“For its time and place there was no other pueblo like Wupatki. It was in all probability the tallest, largest, and perhaps the richest and most influential pueblo in the area.” ~E. Brennan and C. Downum, Report of Findings: Prestabilization Documentation for Wupatki Pueblo

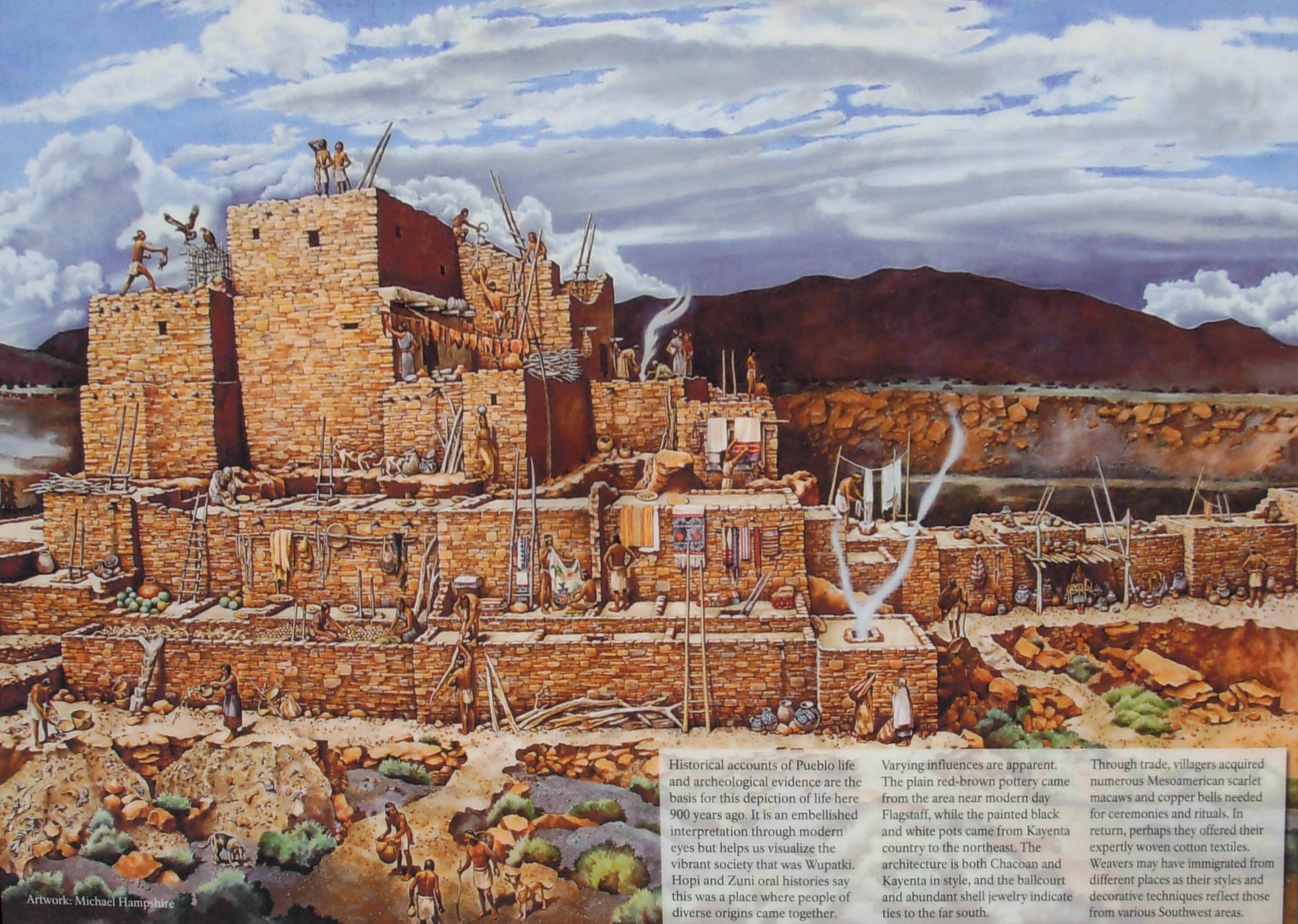

People gathered here during the 1100s and what began as family housing grew into this 100-room pueblo with a tower, community room, and ceremonial ballcourt. Located near the crossroads of east-west and north-south travel routes, the pueblo evolved to serve a community heavily engaged not only in farming but also in ceremony, trade, and crafts specialization. By 1190, as many as 2,000 people lived within a day’s walk and Wupatki Pueblo was the largest building for at least 50 miles.

Archaeologists are challenged to define a cultural identity for Wupatki Pueblo with its intriguing blend of Kayenta and Sinagua architectural styles and more than 100 pottery types.

The name Wupatki derives from Hopi words that translate literally into “it was cut long,” and recalls an event in the histories of the Hopi clans. It is said that people prospered here. In time, men began gambling and ignored their crops and prayers for rain. Concerned, their leader severed a ritual object and then went into exile. When he returned, the people awoke from their decadence.

For today’s Hopi people, the villages of Wupatki remain among the most important “footprints” of the ancestral clans. It was on this landscape, in the shadow of the San Francisco Peaks, that a number of migrating clans met and merged. Significant events, and new traditions and ceremonies resulted. The Zuni and other Puebloan groups (Acoma, Laguna, and Rio Grande) share Wupatki’s history as they share a belief in a common origin that begins with their ancestors. Stories of Wupatki also exist among non-Puebloan groups (Havasupai, Yavapai, Hualapai, Southern Paiute, and Navajo) whose ancestors interacted with Puebloan ancestors. The dates for these interactions are unknown.

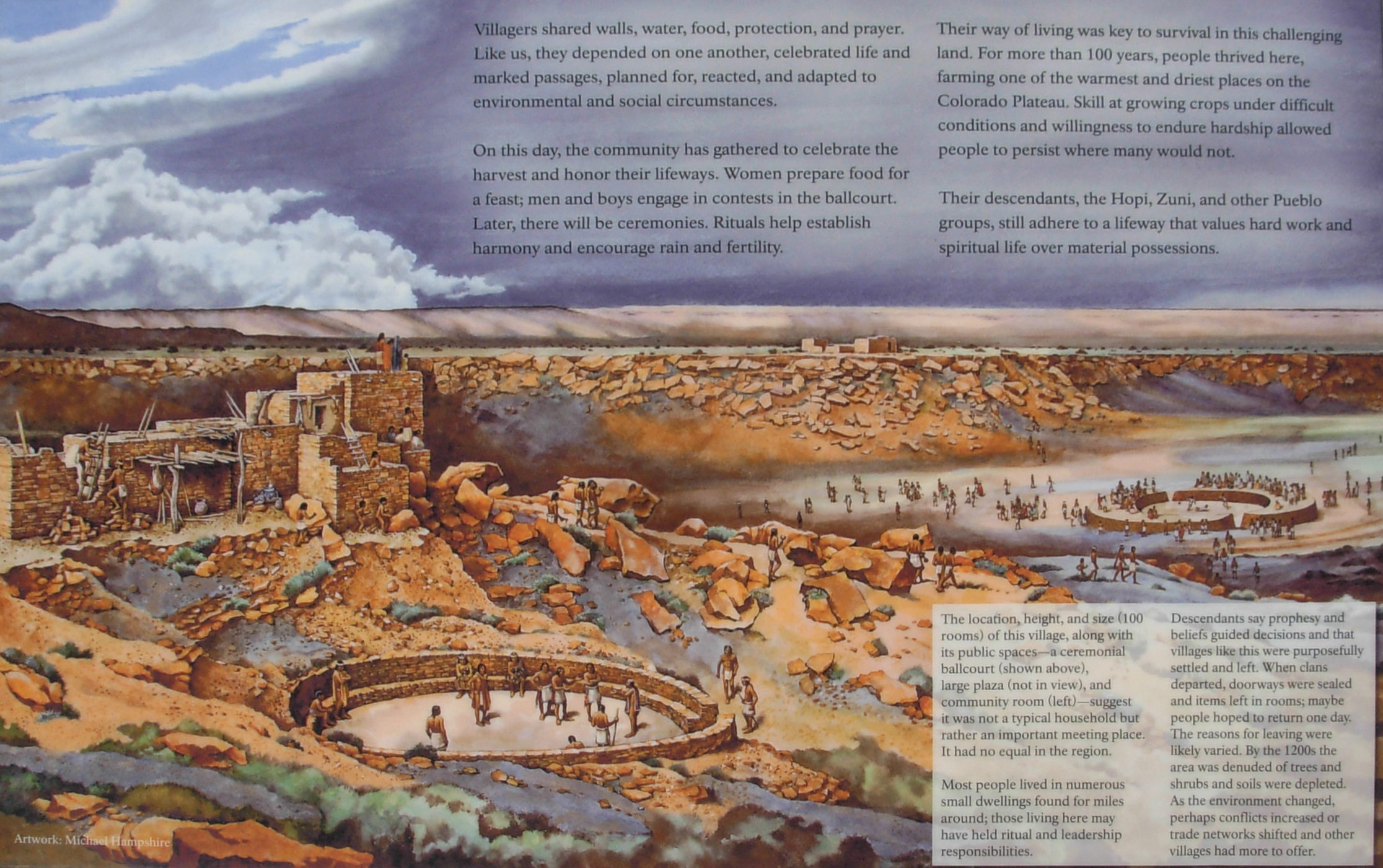

Historical accounts of Pueblo life and archaeological evidence are the basis for this depiction of life here 900 years ago. It is an embellished interpretation through modern eyes, but helps us visualize the vibrant society that was Wupatki. Hopi and Zuni oral histories say this was a place where people of diverse origins came together. Varying influences are apparent. The plain red-brown pottery came from the area of modern day Flagstaff, while black and white pots came from Kayenta country to the northeast. The architecture is both Chacoan and Kayenta in style, and the ballcourt and abundant shell jewelry indicate ties to the far south. Through trade, villages acquired numerous Mesoamerican scarlet macaws and copper bells needed for ceremonies and rituals. In return, perhaps they offered their expertly woven cotton textiles. Weavers may have immigrated from different places in their styles and decorative techniques reflect those from various Southwest areas.

The location, height, and size (100 rooms) of this village, along with its public spaces—a ceremonial ballcourt (shown above), large plaza (not in view), and community room (left)—suggest it was not a typical household but rather an important meeting place. It had no equal in the region. Most people lived in numerous small dwellings found for miles around; those living here may have held ritual and leadership responsibilities. Descendants say prophesy and beliefs guided decisions and that villages like this were purposefully settled and left. When clans departed, doorways were sealed and items left in rooms; maybe people hoped to return one day. The reasons for leaving were likely varied. By the 1200s, the area was denuded of trees and shrubs and soils were depleted. As the environment changed, perhaps conflicts increased or trade networks shifted and other villages had more to offer.

A curious place to build a farming community…summers are hot, dry and windy. Yet 800 years ago, agricultural plots would have dotted the landscape, carefully placed in scant pockets of soil.

A curious place to build a farming community…summers are hot, dry and windy. Yet 800 years ago, agricultural plots would have dotted the landscape, carefully placed in scant pockets of soil.

A farmer’s faith was tested regularly as rainfall came at the wrong time or not at all, and dry winds parched the soil and crops. Each field was at the mercy of where rain fell; no surface irrigation was possible. One field might produce while another withered, so the planting effort was extensive.

Then, as now, water was limited. Across the area, a few seeps and springs existed; catchments held water for a time, and the Little Colorado River provided a seasonal water source.

Still the abundance of storage pots suggests water had to be acquired and managed to be available when needed. Perhaps, as Hopi believe, people derived strength from this challenging land.

The black cinders blanketing the ground remain from the eruption of nearby Sunset Crater volcano some time between 1040 and 1100. The settlement of Wupatki followed but it’s uncertain if there was a direct cause and effect.

The black cinders blanketing the ground remain from the eruption of nearby Sunset Crater volcano some time between 1040 and 1100. The settlement of Wupatki followed but it’s uncertain if there was a direct cause and effect.

People may have been drawn by the eruption and stayed. Or, perhaps those displaced by the eruption moved to this lower elevation. However, as many as three generations may have passed before anyone decided to live here.

We do know that ash from the eruption, in a thin uniform layer, retained precious soil moisture providing a window of improved farming potential in this semi-arid landscape.

“…The family, the dwelling house and the field are inseparable, because the woman is the heart of these, and they rest with her… The man builds the house but the woman is the owner, because she repairs and preserves it.” ~A Hopi view of the community, presented to “the Washington Chiefs,” 1894

“…The family, the dwelling house and the field are inseparable, because the woman is the heart of these, and they rest with her… The man builds the house but the woman is the owner, because she repairs and preserves it.” ~A Hopi view of the community, presented to “the Washington Chiefs,” 1894

Notice how people shaped their lives to this land. Sun, water, wind, and earth influenced decisions. Using the red sandstone outcrop as a backbone, and its naturally fractured blocks as bricks, masons laid stone rooms up and down the length of the formation. High walls on the north and west sides blunted prevailing winds. Terraced rooms to the south and east bathed in winter sun. Flat roofs served as water systems, collecting precipitation and directing it to storage pots.

Wupatki Pueblo stood three stories high in places. Double walls were filled with a rubble core and were about 6 feet (2 meters) high; roofs were constructed with timbers, cross-laid with smaller beams or reeds, and finished with grass and mud. There were no exterior doorways at ground level.

Built out in the open, Wupatki is far more typical of 12th century structures than a cliff dwelling. Cliff dwellings make up only a fraction of known southwestern archeological sites.

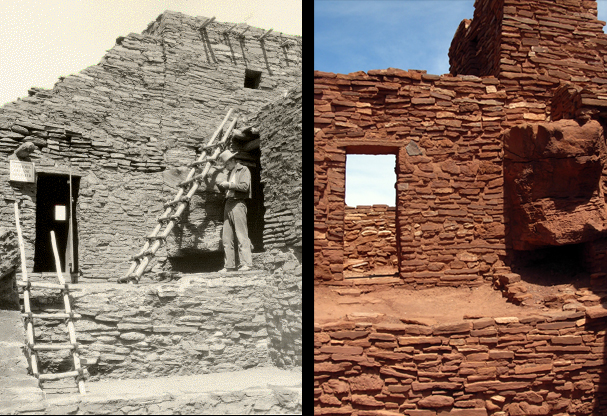

When occupied, this mud and stone building would have required periodic maintenance. Once people departed, natural forces prevailed – mortar eroded, roofs collapsed, walls tumbled. What you see today is an excavated building, heavily stabilized to postpone deterioration.

When occupied, this mud and stone building would have required periodic maintenance. Once people departed, natural forces prevailed – mortar eroded, roofs collapsed, walls tumbled. What you see today is an excavated building, heavily stabilized to postpone deterioration.

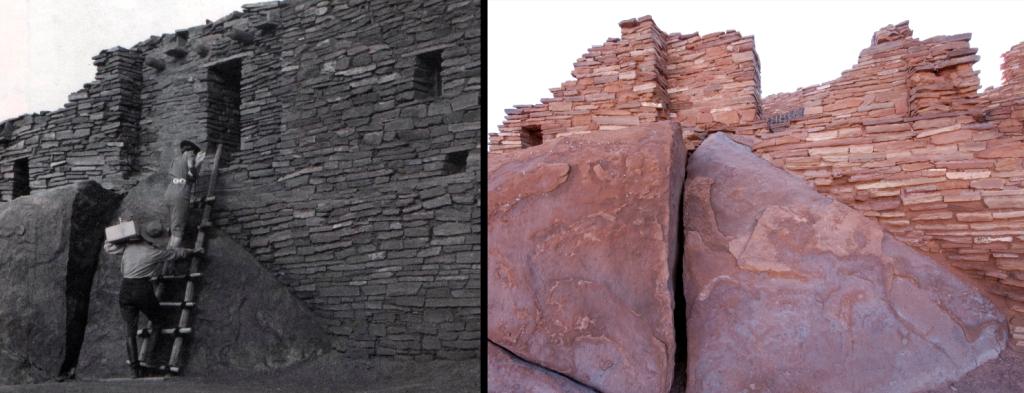

The modern iron beam and plate visible here support the upper walls. The low walls exhibit Portland cement, used from the 1930s to 1960s, and new stabilization mortars that more closely duplicate original materials. Although walls stand in their original location, virtually all the mortar you see is modern. Stabilization has compromised the historical architecture, but helps an excavated building withstand natural and human-induced erosion.

Compare the images above. The rooms now visible were buried beneath rubble cleared during excavation beginning in 1933.

Numerous storage rooms within the pueblo attest to a constant preparedness for crop failure. People likely had some of last year’s corn on hand at this year’s harvest. Perhaps this room served for storage and food processing.

Numerous storage rooms within the pueblo attest to a constant preparedness for crop failure. People likely had some of last year’s corn on hand at this year’s harvest. Perhaps this room served for storage and food processing.

Imagine corn stacked like cordwood, or gathered foods such as piñon nuts, rice grass seeds, and juniper berries secured in clay seed jars. Water jars undoubtedly sat here too. Hours spent at these grinding stones reduced corn and seeds to flour.

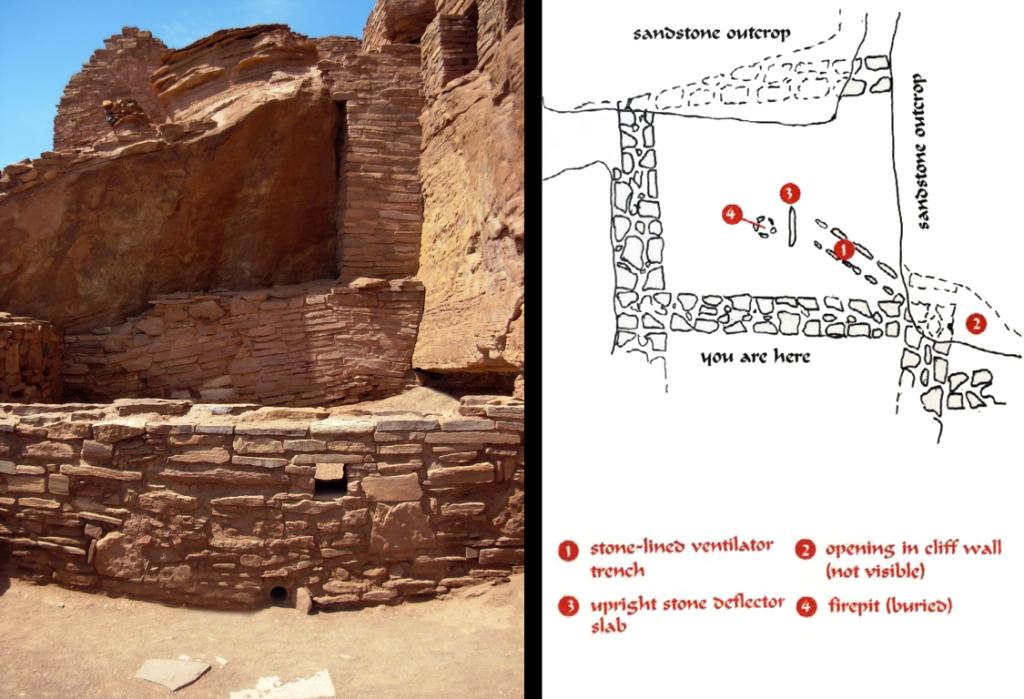

In this room, someone designed an innovative air circulation system to allow for an indoor fire. A stone-lined ventilator trench is connected to an opening in the base of the cliff wall.

In this room, someone designed an innovative air circulation system to allow for an indoor fire. A stone-lined ventilator trench is connected to an opening in the base of the cliff wall.

The upright stone slab at the end of the ventilator trench deflected incoming air so that the draft would pass directly across the firepit. Smoke would exit through a roof opening.

Note how preservation efforts have changed this building: original floor surface, as with this room, are much lower – dirt placed in the rooms after excavation protects floor features and keeps walls from collapsing.

Throughout the dwelling you’ll see a variety of modern drains that keep water from standing in rooms. In some cases the architecture has been altered. For example, the square and round holes on this front wall were placed for drainage, and the large masonry column built in the back corner supports the upper wall.

This section of the pueblo remains unexcavated. These rooms represent an opportunity to learn more about the past, but the knowledge comes at a cost. Excavation disturbs the site, and potentially, the people and artifacts buried there. Collected materials require elaborate conservation and storage methods; in the ground, this arid climate preserves artifacts almost indefinitely, free of charge.

This section of the pueblo remains unexcavated. These rooms represent an opportunity to learn more about the past, but the knowledge comes at a cost. Excavation disturbs the site, and potentially, the people and artifacts buried there. Collected materials require elaborate conservation and storage methods; in the ground, this arid climate preserves artifacts almost indefinitely, free of charge.

In the past, few people challenged the purposes of archaeological investigation, but today many voice concerns about disturbing sites. Should rooms be excavated, unearthing pots and other items? Possessions were intended, by those who buried or left them behind, to remain as placed, acted upon by time and the elements. Excavation represents a curiosity foreign to American Indian culture and often considered culturally offensive. Do objects from the past serve as legitimate educational tools, or is that notion unimportant or even wrong?

The reconstructed circular structure below you resembles a great kiva, a special room used for rituals and ceremonies. However, excavators found no evidence of a roof or other floor features typical of a kiva. Archeologists speculate that this open-air community room could have served as a central gathering place. Imagine voices carrying to others assembled on the pueblo roof tops.

The reconstructed circular structure below you resembles a great kiva, a special room used for rituals and ceremonies. However, excavators found no evidence of a roof or other floor features typical of a kiva. Archeologists speculate that this open-air community room could have served as a central gathering place. Imagine voices carrying to others assembled on the pueblo roof tops.

People may have come from nearby and distant villages to participate in ceremonies held here. Maybe rituals focused the community and solved problems, or served to redistribute materials and food.

Other people have come and gone since the original occupants. During the late 1800s, Basque sheepherders stayed here briefly, enlarging this doorway and occupying the room beyond. Local prospector Ben Doney pothunted Wupatki, amassing an impressive collection of artifacts.

Other people have come and gone since the original occupants. During the late 1800s, Basque sheepherders stayed here briefly, enlarging this doorway and occupying the room beyond. Local prospector Ben Doney pothunted Wupatki, amassing an impressive collection of artifacts.

Concern over looting at Wupatki led to its protection as a national monument in 1924. Later expansion of the monument included some land historically used since the mid-1800s by Navajo naat’ áanii (headman) Peshlakai Etsidi and his descendants. These Diné families grazed sheep here, moving seasonally between numerous camps, leaving behind more than 60 residential sites. Their history is intertwined with that of the monument. They remain intimately tied to the Wupatki landscape.

Rooms on this end of the pueblo were excavated and reconstructed to serve as an office and museum. The National Park Service now has a policy of stabilizing buildings in their existing state. The 1930s reconstructions were removed in 1950.

“We found… all the prominent points occupied by the ruins of stone houses of considerable size… They are evidently the remains of a large town, as they occurred at intervals for an extent of eight or nine miles and the ground was thickly strewed with pottery in all directions.” ~Journal entry, Sitgreaves Expedition, October 8, 1851

“We found… all the prominent points occupied by the ruins of stone houses of considerable size… They are evidently the remains of a large town, as they occurred at intervals for an extent of eight or nine miles and the ground was thickly strewed with pottery in all directions.” ~Journal entry, Sitgreaves Expedition, October 8, 1851

The extent of this community is not obvious, but hundreds of small family dwellings surround us forming a cluster. Another cluster exists on the uplands to the west (where you may visit Citadel and Lomaki Pueblos). We don’t know if the Wupatki and Citadel communities were autonomous, cooperatives, or competitors.

From this point, you can see two other nearby homes. These sites are not open to visitation.

The reconstructed ballcourt was an unusual structure. Known ballcourts in the Southwest were not masonry. This court may have had multiple functions: a place where special ceremonies were held, where competitive games took place for socialization, or where children played a game of stick and ball, similar to hockey. After rains, it may have served as a reservoir.

The reconstructed ballcourt was an unusual structure. Known ballcourts in the Southwest were not masonry. This court may have had multiple functions: a place where special ceremonies were held, where competitive games took place for socialization, or where children played a game of stick and ball, similar to hockey. After rains, it may have served as a reservoir.

Some archaeologists think valuables changed hands through ritual events such as ball games. People living to the south (Hohokam tradition) had shells, salt, cotton, and a ballcourt in every town. People to the east in the Chaco region (Ancestral Puebloan tradition) has Mesoamerican macaws, copper, and turquoise to trade. A ballcourt at Wupatki could function as a link between distant regions. Trade valuables from both regions ended up here.

Sandals trod far and wide, maintaining trade networks that helped meet mutual needs and improved the quality of life. When materials, innovations, and ideas came to communities, all knew what others had to offer.

Ballcourt at Wupatki Pueblo. The Wupatki ballcourt is 78 feet wide, 102 feet long, and had a 6-foot-high wall. Excavated and stabilized in 1965, a large part of the interior wall has been reconstructed.

Ballcourts were common in southern Arizona from A.D. 750 to 1200, but relatively rare here in the northern part of the state. This suggests that the people of Wupatki intermingled within their southern Arizona neighbors – the Hohokam – who may have borrowed and modified the ballcourt idea from earlier contact with the Indian cultures of Mexico.

Located along major natural drainages and travel routes, ballcourts may have provided opportunities for social exchange between villages. They were often within a one-day walk of a neighboring village.

There is continued speculation about the uses of the ballcourts. Because of the work involved in building a ballcourt and the numbers that have been found (over 200 in Arizona), ball games may have been an important part of life for the people of Wupatki and their southern neighbors.

The Hohokam balls – found at archaeological sites containing ballcourts – were made of carefully shaped rock and perhaps covered with pin pitch or other material. One form of the game might have involved moving the ball toward a goal using a curved stick.

This depiction of a ball game is based on descriptions of games played by the Mayan and Aztec cultures of Mexico and speculations on the Hohokam games in southern Arizona.

An intriguing geological feature—the blowhole—was unearthed during the 1965 excavations of the Wupatki ballcourt. After its discovery, the National Park Service bricked in the opening, giving the blowhole the appearance it has today and allowing visitors the experience of feeling the rush of air from the opening.

It is unknown if the people of Wupatki were aware of the blowhole, and if they were, what significance the feature may have held to prehistoric people.

This blowhole—a crevice in the earth’s crust that appears to breathe—is one of several found in the Wupatki area. It connects to an underground passage—size, depth, and complexity unknown—called an earthcrack. Earthcracks resulted from earthquake activity in the Kaibab Limestone bedrock and have enlarged over time.

Archaeologists have yet to uncover any evidence of prehistoric structures or uses at the blowhole. Its connection to the Wupatki Pueblo remains a mystery.

Today, the Hopi descendants of these early people, refer to the blowhole as the breath of “Yaapontsa,” the wind spirit. They and other American Indians attach a spiritual significance to these features.

People were often buried in rooms such as this; consequently, graves and beliefs were inadvertently violated when this site was excavated. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Ace of 1990 (NAGPRA), asserts that the present day American Indian tribes affiliated with archaeological sites have rights and beliefs to be protected. This Act helps ensure that decisions about these places reflect the values and wishes of those who were here before.

People were often buried in rooms such as this; consequently, graves and beliefs were inadvertently violated when this site was excavated. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Ace of 1990 (NAGPRA), asserts that the present day American Indian tribes affiliated with archaeological sites have rights and beliefs to be protected. This Act helps ensure that decisions about these places reflect the values and wishes of those who were here before.

As tribes exert more control over their heritage, diverse opinions about appropriate treatment of archaeological sites emerge. As an example, most Puebloan groups believe if human creations were made to last forever and not let to die, “the world would get filled up, and the purpose of living would disappear.” This philosophy challenges National Park Service mandates to preserve and perpetuate the physical remains of the past.

“…the man cultivates the field, but he renders its harvests into the woman’s keeping.” ~A Hopi view of the community, 1894

“No woman ever sat at the Hopi looms. The men were expert weavers; they wove diligently all winter long in the various kivas. Hopi woven items were known far and wide, and people of other tribes came to barter for them.” ~Helen Sekaquaptewa, from “Me and Mine”

The open plaza area may have been the hub of village life and work. Ethnographic evidence suggests most activities were gender specific, and everyone contributed. Children learned by watching, listening, then doing. Surely there were no idle hands. Women worked clay into necessary utensils. They mortared the pueblo, knowing clay as they did. As the herbalists, gatherers, and protectors of stored crops and seeds, women were vital to the community. Men hunted and farmed. The entire growing season may have been spent away from home tending fields. Winter brought with it time to weave. Fine cotton textiles and abundant tools suggest weaving was an important, highly developed skill at Wupatki.

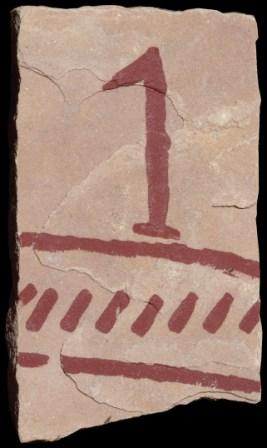

Along this side of the pueblo, people repeatedly dumped their trash, forming a midden. Refuse tells us much of what we know about past life. Each layer of food debris yields facts about diet, nutrition, and changing reliance on resources throughout the history of the village. Broken pottery and worn out tools reveal relative dates of occupation and technological changes through time.

Along this side of the pueblo, people repeatedly dumped their trash, forming a midden. Refuse tells us much of what we know about past life. Each layer of food debris yields facts about diet, nutrition, and changing reliance on resources throughout the history of the village. Broken pottery and worn out tools reveal relative dates of occupation and technological changes through time.

When Wupatki was excavated, artifacts and food remains were collected and stored but not studied for years. Today, rather than excavating new material, we study old collections to learn how people altered or managed plant and animal populations to their advantage.

This midden has not been excavated. Walking off trail here, or through any midden, mixes the upper layer of trash with lower levels, destroying the context that is so important to understanding past lifeways.

You may enter this room. The rock outcrop around you provided an almost ready-made room, initially used for household trash. Roughly 5 feet (1.5 meters) of debris accumulated here before the first floor was laid and the space used as a living room. Can you tell where a second story room began?

You may enter this room. The rock outcrop around you provided an almost ready-made room, initially used for household trash. Roughly 5 feet (1.5 meters) of debris accumulated here before the first floor was laid and the space used as a living room. Can you tell where a second story room began?

This room provides a special opportunity to experience the pueblo in an intimate way. Generally, you should not enter rooms unless invited. Everyone has a responsibility to know the “ground rules” when visiting an archeological site.

“Those were the two rooms we were to live in. At the top of the ladder was the room used as a bedroom and office, and (to the right) the beautiful sunny little kitchen. The water was in a barrel behind a niche in the kitchen wall… Davy pumped the water in once a week, fifty-five gallons, and that sufficed for everything. We took our baths there unless it was a special occasion, when we would go down to where the spring ran out to the sheep troughs. There was more water that way, but there were apt to be sheep and Navajos, too.” ~Corky Jones, from Letters from Wupatki

“Those were the two rooms we were to live in. At the top of the ladder was the room used as a bedroom and office, and (to the right) the beautiful sunny little kitchen. The water was in a barrel behind a niche in the kitchen wall… Davy pumped the water in once a week, fifty-five gallons, and that sufficed for everything. We took our baths there unless it was a special occasion, when we would go down to where the spring ran out to the sheep troughs. There was more water that way, but there were apt to be sheep and Navajos, too.” ~Corky Jones, from Letters from Wupatki

Park rangers once lived in this pueblo. The two rooms above were reconstructed to house employees Jimmy and Sallie Brewer, and Davy and Corky Jones during the 1930s. They hauled water from the nearby spring, but had the luxury of cooking with propane. Jones excavated a small adjoining storage room to house a gas refrigerator; commercial electricity did not arrive until 1959. The government, of course, charged them rent – $10 per month!

Reconstructed rooms may help us to visualize the past and identify more closely with the inhabitants. But, the mental images we construct and conclusions we draw likely mirror our present rather than reflect the world in which they lived. Reconstructions lead us to believe we know the past, when in reality, so much will never be known. Like other reconstructions, these walls and roofs were removed in the 1950s.

The two beams at the rear of the room above have been in place for 800 years. Tree-ring dates obtained from various beams in the pueblo span from 1106 to 1220 but cluster around three periods: 1137, 1160, and 1190. This suggests specific periods of construction, or at least beam cutting. Many room walls also abut one another-evidence that a room was added on to one already in place. Perhaps the various building phases mark the arrival of clans, each bringing something different to the community, resulting in the “cultural brew” that makes Wupatki so unusual. Some archeologists see cultural traditions, such as Sinagua and Kayenta, not as “people” or genetic and ethnic groups, but rather as inhabited geographic regions experiencing a dynamic ebb-and-flow of populations. Migrations brought people together creating cultural dominance in some areas and shared cultural traits in others. Seen this way, specific traditions such as black-on-white pottery and T-shaped doorways could have been maintained over centuries by peoples of different linguistic and ethnic backgrounds.

The two beams at the rear of the room above have been in place for 800 years. Tree-ring dates obtained from various beams in the pueblo span from 1106 to 1220 but cluster around three periods: 1137, 1160, and 1190. This suggests specific periods of construction, or at least beam cutting. Many room walls also abut one another-evidence that a room was added on to one already in place. Perhaps the various building phases mark the arrival of clans, each bringing something different to the community, resulting in the “cultural brew” that makes Wupatki so unusual. Some archeologists see cultural traditions, such as Sinagua and Kayenta, not as “people” or genetic and ethnic groups, but rather as inhabited geographic regions experiencing a dynamic ebb-and-flow of populations. Migrations brought people together creating cultural dominance in some areas and shared cultural traits in others. Seen this way, specific traditions such as black-on-white pottery and T-shaped doorways could have been maintained over centuries by peoples of different linguistic and ethnic backgrounds.

This room, on the southeastern corner of the pueblo, is one of the largest in the village, yet no household tools or utensils were found inside. This suggests it was a special space, perhaps a ceremonial room known as a kiva. However, a kiva would have a single bench on the north side of the room. There is no record of this, but early excavations may have missed such a feature. In a village this size, one or two kivas would have been expected. They may have been used for the private aspects of ritual, while the larger, open community room served public ceremonies.

This room, on the southeastern corner of the pueblo, is one of the largest in the village, yet no household tools or utensils were found inside. This suggests it was a special space, perhaps a ceremonial room known as a kiva. However, a kiva would have a single bench on the north side of the room. There is no record of this, but early excavations may have missed such a feature. In a village this size, one or two kivas would have been expected. They may have been used for the private aspects of ritual, while the larger, open community room served public ceremonies.

Today, rectangular clan kivas persist in Hopi villages, while larger, round community kivas endure in the eastern Pueblos. Kivas are an integral part of Puebloan society and remain a cultural trait that can be traced from past to present.

Compare the possible kiva to the room to the left. Note the size difference? The inset shows the interior hearth (firepit) and deflector.

“…for us life is shrouded in mystery and the world defies explanation…humans do not need to know everything there is to be known. The human past, we feel, is a universal past. No one can claim it, and no one can ever know it completely.” ~Rina Swentzell, Pueblo Santa Clara

“…for us life is shrouded in mystery and the world defies explanation…humans do not need to know everything there is to be known. The human past, we feel, is a universal past. No one can claim it, and no one can ever know it completely.” ~Rina Swentzell, Pueblo Santa Clara

Villages like Wupatki were purposely settled and left for reasons we may never fully understand. After roughly 150 years here, maybe life ceased to be good. Perhaps the rumor of a better life in another village was worth investigating. Maybe, as some Hopi believe, the people stayed too long here and failed to lead moral and responsible lives. Ensuing social and environmental catastrophes were signals to resume migrations to find and settle the place where Hopi live to this day.

By 1300, across the region people had moved into villages even larger than Wupatki. Those living here joined others at places like Homol’ovi along the Little Colorado River (near present day Winslow, Arizona) or at villages south of Walnut Canyon. According to clan histories, some went directly east to the Hopi Mesas. A few undoubtedly chose to stay behind.

Today this village rests silent but not forgotten. Though it is no longer physically occupied, Hopi and Zuni people believe those who lived and died here remain as spiritual guardians. Descendants visit periodically to enrich their personal understanding of their clan histories. Wupatki is remembered and cared for, not abandoned.